by Scott Raia

This essay uses phenomenological psychology to examine the themes of Michel Gondry’s 2004 film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, specifically the associationist and cognitivist schools of psychoanalysis. This essay observes the film’s claim that real-world suppression of memories is impractical and dangerous. This essay investigates some of the film’s allusions, including the poem by Alexander Pope from which the film derives its title, as evidence of the film’s stance against attempts to remove painful memories. This essay concludes with a subjective reading of the film text’s implications that support the theme that memories are integral to identity.

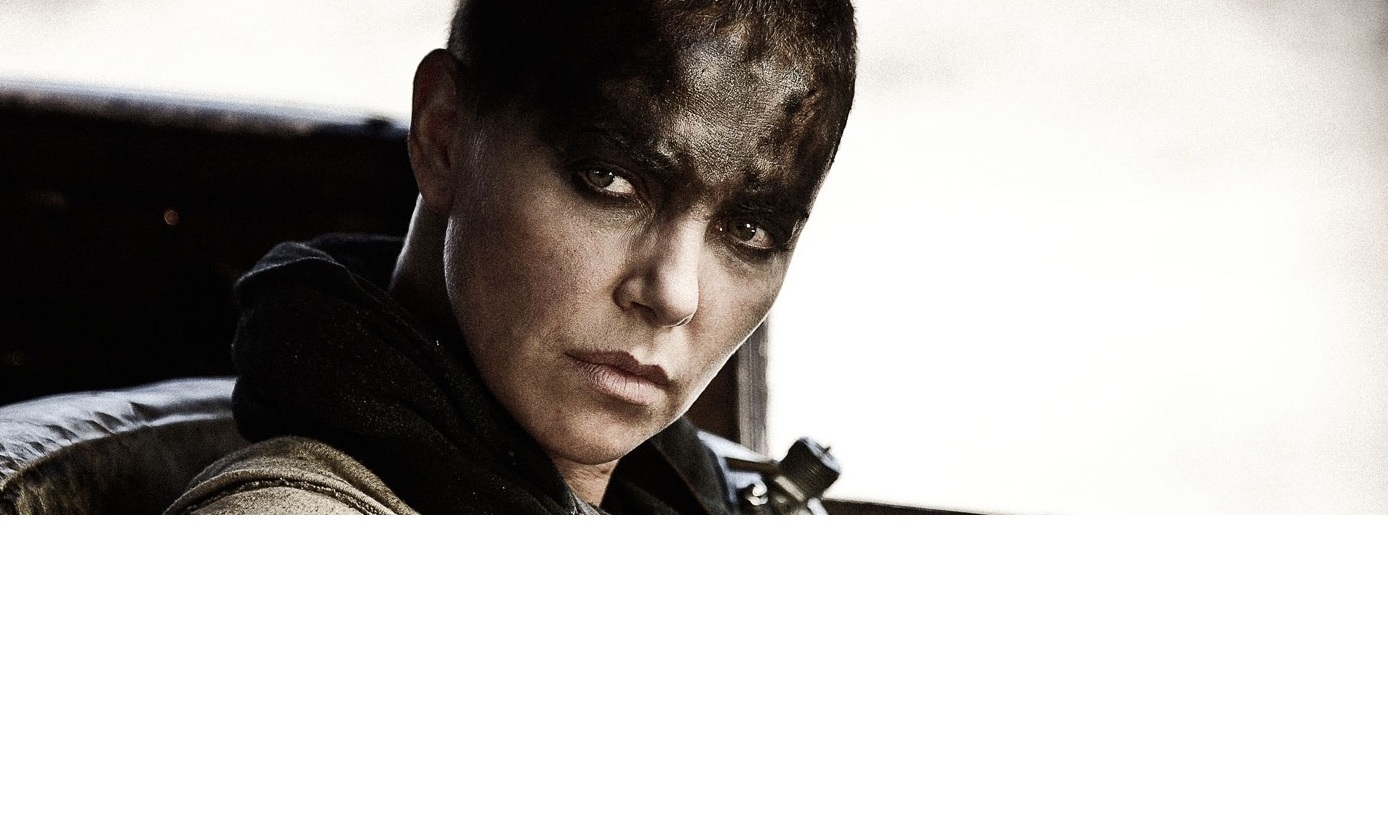

What makes a person who they are apart from their memories from past experiences? Michel Gondry’s film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) begins to answer this question by examining memory cognition and exploring the disadvantages of suppressing or erasing memories. After a harrowing breakup, Joel and Clementine (Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet) appealed to a neuroscientist at Lacuna, Incorporated to delete each other from their memories. (A “lacuna” is a gap or unfilled interval where something is lost or missing.) The film follows Joel in his sedated mind as the technicians slowly administer the procedure one night. As Joel relives the memories being deleted, he begins to regret his decision to erase Clementine from his mind and unsuccessfully attempts to call it off. As the couple eventually find their way back to each other, they recognize that they cannot fully forget their shared experiences because a person’s identity is solely a sum total of their past experience.

By considering the film’s nuances and its cultural allusions, the active viewer of Eternal Sunshine understands the film’s stance that obliterating people and events from memory is unwise and ineffectual. Additionally, when the film is examined through the lens of phenomenological psychology, specifically using the associationist and cognitivist approaches, the film asserts that memory is subjective and fallible in both its cognition and recollection because people’s memories—their collective past experiences—comprise what makes them who they are and what makes them fully human. Thus, by identifying the relevancy of a phenomenological approach, I seeks to explore the unfeasibility of erasing memory while keeping the self’s identity intact.

Phenomenology is an approach to psychology that studies the structures of consciousness people experience from first-person perspectives (Smith). Those in this field of study observe the processes of sensation and perception, and the storage and recollection of cognized memories by association. Memories hold a place in the dichotomy between sensation and perception because they represent perceptions that have been encoded and stored, which are re-experienced and re-perceived upon contemplation. As one experiences reality, one senses, then perceives, and then reflects. This reflection occurs non-chronologically and by association in a fragmented mode of consciousness, which Eternal Sunshine communicates through its non-chronological narrative structure that lacks clear cause and effect.

Eternal Sunshine utilizes non-linear chronology to recount the narrative, which illustrates the associational qualities of memory encoding and recollection. Snippets of the story are arranged in the plot in a strategic order to reveal narrative, character, and theme. The film observes the non-chronology of the storage and retrieval of memories in propagation of a principle English philosopher David Hartley, founder of the Associationist school of phenomenological psychology, called the association of ideas. Hartley formulated the idea that as an individual perceives the world, he or she associates perceptions with related thoughts, memories, and feelings and stores the perceptions with a neurological link to those impressions in the brain. Later, external events trigger the recollection of those associations, causing a chain reaction from one memory to another. Segments of memory are presented in relation to Joel’s emotional mindsets and not in linear order. Some of the memories with Clementine are commonplace occurrences, which are used to provide an accurate portrayal of the typicality of their couple’s relationship, but most of the memories are landmarks of the relationships because they are moments of the greatest emotional impact. As Joel had hoped, the memories associated with pain are erased from his mind, but the memories associated with joy and pleasure are erased along with the painful ones.

The technicians in Eternal Sunshine apply the procedure indiscriminately to all of Joel’s memories of Clementine, both positive and negative, which proves to be detrimental to Joel’s happiness and well-being. The technicians use Joel’s mementos of Clementine to trigger associations in his brain that they map using an EKG. As they later target and destroy specific coordinates in Joel’s brain, he relives the memories that exist there. Nearly all of the memories shown in the labyrinth of his brain regard some event that was emotionally significant. Because of the turbulent nature of the relationship, most of these memories include feelings of anger, embarrassment, or jealousy. However, as these memories are deleted, Joel also recollects fond memories, which make him nostalgic of the positive side of his relationship with Clementine. When he remembers an instance when she let down her wall and shared with him a difficult, character-defining moment in her childhood, he desperately pleads, “Please, let me keep this memory.” By blocking everything relating to Clementine from his memory, Joel loses more than the painfully associated experiences, but also the more precious and important, happy memories that made him the man he was.

As clearly as the associational approach exposes the nature of memory cognition and recognition, the cognitivist school of phenomenological psychology reveals the subjective nature of encoding and recalling memories. The recording and recollection of memories is vulnerable to influence from one’s present mental and emotional climates, making them unreliably subjective. Even if recollection were infallible, the continuous perception of reality is constantly tinted by attitudes, values, and past experiences. In perceiving the external world, one cognizes reality once with one’s sense organs in the ever-elusive present and again upon reflection. Memory is therefore a subjective copy of a subjective copy, which accounts for incongruities between the transpiration of past events and one’s reminiscent discernment of those events. The human mind first senses stimuli such as light or sound, which are perceived and interpreted by synthesis with past experiences, encoded, and logged into memory centers in the brain. When associative triggers are later initiated, the mind recalls the memories through reflection and reinterprets these memories in light of current mental and emotional climates. Reflection can produce interpretations of past events that are vastly different from the initial interpretations. Rumination on the past reveals details in memories that had been previously unnoticed or ignored, allowing one to reconstruct, re-experience, and reinterpret the memory in a new contextual perspective.

As Joel’s memory is erased, he experiences just such reinterpretation of past memories while revisiting events with Clementine that had previously caused him emotional discomfort; this in turn illustrates the flawed thinking behind consciously blocking memories. However, his consciousness of the deletion subverts his cynicism toward the memories because he is frantic to preserve his memory of her. He reexamines Clementine’s idiosyncrasies that he previously disliked and begins to remember them fondly. For example, he remembers his first meeting with Clementine when she grabs a piece of chicken from his plate with little warning. Originally, Joel was uncomfortable with her interacting with such familiarity and forwardness at this first meeting. However, as he reflects on the incident in light of its deletion from his memory, he re-experiences it with fondness and nostalgia. He wishes he could keep this idiosyncratic memory of Clementine, illustrating the absurdity at the core of attempting to remove people or events from one’s memories of the past; that is, even unpleasant memories can be perceived positively under the right circumstances.

While the film certainly asserts that to block memories is unwise, it also implies that memory erasure after a breakup is possible to smaller extents. Obviously, the kind of total memory deletion in Eternal Sunshine only exists in the movies, but, to a degree, a similar process is possible in reality. As an individual recovers from a traumatic separation, his or her natural tendency is to dispose of that relationship’s tokens of memento such as photos, gifts, and letters in an attempt to “erase” the loved one from memory. According to a case study at the University of California, Santa Cruz, the disposal of these symbolic items is actually a rather successful tool in forgetting a breakup (Sas and Whittaker 2-3). The procedure at Lacuna involves collecting and disposing of the relics around the patient’s home. While the real world application of this disposal does not literally delete the memories from the mind like it does in the film, it does eliminate from people’s minds the relics that trigger the painful emotions associated with them and reduces the likelihood of repeatedly eliciting their recollection. After a traumatic separation, one will find one’s mind returning continually to memories shared with a loved one. One might correctly feel like such associative remembrance is largely outside of one’s control. But, in another act similar to Lacuna’s memory erasure, as time progresses, the psyche is trained to curtail and avoid recollections of emotionally painful memories. Psychologists call this phenomenon repression, which is an observation at the cornerstone of psychoanalysis. In this way, certain events are blocked from memory, making absolutely possible their relative “deletion” (Loftus 13-15).

While this deletion can take place in the real world to small degrees, Eternal Sunshine argues that it is impossible to erase people and events from memory while keeping intact one’s identity. As Joel’s memory is being erased, he interacts with his memory of Clementine, which is personified by Kate Winslet even though she is just a memory. He agrees with the manifestation of his memory of Clementine that he will meet her at the place of their first acquaintance. The morning after his operation, Joel impulsively skips work and takes a train to Montauk, where he re-meets Clementine. The fact that Montauk lies far removed from both of their daily lives indicates that this meeting is anything but a coincidence. Despite their deletion from each other’s memories, the two conflicted lovers eventually find their way back to each other’s arms, illustrating the film’s claim that total annihilation of memories and their psychological imprints is impossible because they become an integral part of personal, social, and cultural identity. Film critic Gary Simmons comments on the film’s stance: “Shared experience can be dulled, but never forgotten, because it has been lived. There is no on/off switch in human beings” (Simmons 2). While the film’s plot makes possible the thorough erasure of memories, the message of the film in relation to the possibility of such erasure is clear: identity is a construction of multiple memories, individuals cannot erase parts of their memories without fundamentally changing their identity. The people in one’s life and memory make up one’s thoughts and values.

In addition to conveying a message about the possibility of memory erasure, the film also examines the negative utility of erasure. In Eternal Sunshine, the doctor’s receptionist, Mary (Kirsten Dunst), quotes lines from Alexander Pope’s poem (from which the film derives its title) entitled “Eloisa to Abelard” that typifies the philosophy of the two pained lovers and the company who erases their memories:

How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot!

The world forgetting, by the world forgot.

Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind!

Each prayer accepted, and each wish resigned . . .

(Pope ll. 207-10)

The poem is a fictional epistle from a woman, Eloisa, to her once lover Abelard, who has been brutally castrated by Eloisa’s disapproving family and enters a monastery after losing his romantic feelings. The text is a distraught song of Eloisa’s struggle to reverse her passion for Abelard, and in doing so she finds respite in forcing herself to forget. In reference to her attempt to forget, she mentions a “calm, eternal sleep, where grief forgets to groan, and love to weep” (Pope, ll. 313-14). Eloisa not only forgets the pains of grief, but also the joys of love. All emotional extremes—high and low—are numbed as she forgets Abelard, not unlike the process of drowning one’s sorrows in the nepenthe of alcohol. And just like that of an alcoholic escape, the usefulness and wisdom of Eloisa’s choice to suppress her memory of Abelard is controvertible.

The subtle motif of alcohol in the film propagates the theme that numbing pain through forgetting does not solve the pain’s underlying problems. When Dr. Howard Mierzwiak explains the procedure for memory erasure, Joel expresses worry about the possibility of brain damage. Howard tells him that, technically, the operation itself is brain damage on par with a night of heavy drinking. From an early point in the film, the filmmakers compare the calculated destruction of memories in the operation with the destructive numbing of drinking alcohol. At the end of the film, when Joel and Clementine listen to the tape from Joel’s Lacuna files together, Joel offers her something to drink. She asks for whiskey because she is in an uncomfortable situation and wishes to numb her pain. The comparison of suppressing painful memories to suppressing emotional discomfort by drinking creates an analogy that is accessible to many. Most people know of the danger of trying to escape from problems using alcohol. And trying to escape from painful memories by forgetting them is, according to the film, equally unwise.

The conscious choice to subdue all memories of a former companion without consideration of their positive or negative emotional connotations reflects an attitude contradictory to the popular idiom, “It is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all” (Tennyson). As Joel sits in the waiting room at the Lacuna office, a woman waits next to him in tears holding a box of her deceased pet’s belongings. The philosophy of pet ownership typifies the attitude that it is better to love and lose than to abstain from love altogether because zoophiles adopt pets with a full knowledge that their own lifetimes will almost certainly outlast those of their dear companions. The woman in the waiting room knew she would survive her pet and live to mourn its death, yet she chose to adopt anyway. Her presence in the Lacuna office may represent, like it did for Clem and Joel, a hasty, emotional decision while facing the pain of her lost pet. Similarly, at the film’s conclusion, despite the negative assurances they hear in the tape recordings they made before their operations that the relationship will be a rollercoaster likely to end in agony, Joel and Clem consciously decide to revamp their relationship. They trust that the joy will be worth the subsequent pain. In the words of the title of a Robert Frost poem, “Happiness Makes Up in Height for What it Lacks in Length” (178).

Eternal Sunshine’s themes contradict Eloisa’s praise of the process of forgetful ignorance because the film seems to declaim the utility of deleting memories. As Joel forgets his painful past with Clementine, he loses many fond memories along with the painful ones. Naturally, he remembered only the painful experiences and disregard the rest directly after the breakup, and it was not until he faces the loss of all of his memories with Clementine that he remembers and longs to preserve the fond ones.

Thus far in this essay, I have observed the film text, but will now shift from formative examination to substantive commentary informed by my semi-liberal interpretation. In reference to this kind of shift in discussion, film theorist Dudley Andrew comments that “structuralism and academic film theory in general have been disinclined to deal with the ‘other-side’ of signification, those realms of pre-formulation where sensory data congeal into ‘something that matters’ and those realms of post-formulation where that ‘something’ is experienced as mattering” (Andrew 627). The following is my sub-textual interpretation in light of my personal experience, values, and taste, which may or may not be consistent with other critics’ interpretations of the film.

A review of Joel and Clementine’s relationship reveals that it was anything but healthy and stable. Conceived in weakness and insecurity, their relationship was doomed from the beginning; before meeting Clem for the first time, Joel writes in his journal that he was considering returning to his previous girlfriend because of his loneliness. The film shows the blustery breakup the couple undergoes. After Clementine goes out one night without Joel, she comes home severely inebriated at 3:00 a.m. and informs Joel that she has wrecked his car in front of his apartment. This leads to a brief verbal altercation, which comes to a point when Joel stoops to attack Clementine’s sexuality. Hurt, she storms out despite Joel’s profuse apologies.

This quarrel was not an anomaly. As Joel relives his past with Clementine, he remembers many other instances when their personalities clash, such as hurtful personal attacks in moments of vulnerability and a loud, heated argument on a crowded public street. But Joel and Clem both forget these uncomfortable experiences just like every other shared memory. They therefore had no internal mechanism to prevent them from returning to such fickle codependency, and obliviously reunite. The two end up reentering an unstable, unhealthy relationship because they have no remnant of the pain it caused them to warn them against it.

Our brains store memories associated with the sensations that accompany them. For instance, anyone who has touched a hot stove knows never to do it again because it is associated with physical pain. Feelings of guilt also function to motivate the remediation of behavior that is in conflict with our system of morality. Eliminating these guiding experiences from memory is therefore counterproductive because it removes the mechanism that helps prevent us from repeating mistakes.

The escape from memories that shape experience appears to be an opportunity to return to an innocent and childlike “spotless mind,” or, in the words of philosopher John Locke, a tabula rasa—a blank slate. Locke maintains that we are all is born with no preconceived ideas or innate tendencies, but that these are instilled in them as life progresses. The idea of returning to a blank slate is truly beguiling (albeit implausible), yet this infinite horizon implies other unintended consequences. Those scars in our past that we wish so eagerly to forget actually shape our identities and make us wholly human; forgetting and being forgotten make us truly empty and blank inside. Those lapses in memory where we chose to forget past pains are actually lacunas in the figurative DNA that codes for character and personality in the present. Therefore, to infantilize the human mind through disremembering is futile.

Works Cited

Andrew, Dudley. “Phenomenology: The Neglected Tradition.” Ed.Bill Nicholas. Movies and Methods Volume II. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978. 628-31. Web.

Edwards, Kim. “White Spaces and Blank Pages: Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.” Screen Education. (2008). Pages? Web.

Frost, Robert. Frost: Collected Poems, Prose and Plays. Chicago: Henry Holt and Company, 1969. Print.

Gondry, Michel, dir. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Focus Features, 2004. Film.

Hartley, David. Observations on Man, his Frame, his Duty, and his Expectations. MA thesis. University of Birmingham, 1749. London: Samuel Richardson. Web.

Locke, John. Two Treatises of Government. 1st. 2. London: Awnsham Churchill, 1689. Web.

Loftus, Elizabeth. “The Reality of Repressed Memories.” American Psychologist. 45.5 (1993): 13-5. Web.

Pope, Alexander. “Eloisa to Abelard.” 1717. Complete Poetical Works. 1903. Web.

Sas, Cornia and Steve Whittaker. “Design for Forgetting: Disposing of Digital Possessions After a Breakup.” Paris, France: 2013. 2-3. Web.

Simmons, Gary. “Memory & Reality in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.” Screen Education. (2009): Pages 1-6. Web.

Smith, David Woodruff. “Phenomenology.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2013.

Tennyson, Alfred Lord. “Memoriam 16: I envy not in any moods.” Poem Hunter. Web. 22 Mar 2014.