by Kaily Goodro

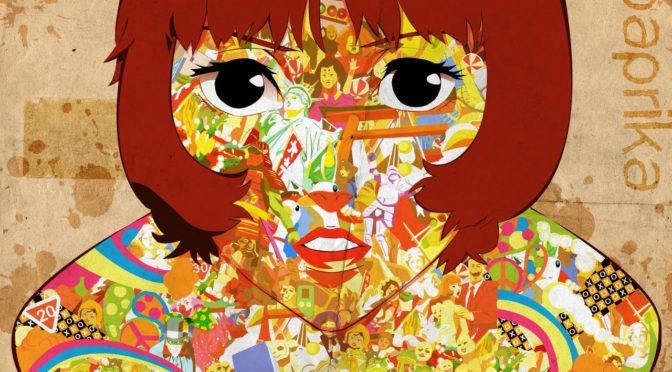

Jean-Louis Baudry’s apparatus theory suggests that movie viewers experience an immobility that makes watching a film akin to dreaming. Spectators are unable to freely move, unable to affect what they see, and unable to differentiate between self and other as well as the ideologies of a film and their own thoughts. Theorists like Noël Carroll criticize Baudry’s concept, claiming that viewers maintain at least limited movement while watching a film and, therefore, retain ideological autonomy. Director Satoshi Kon’s Paprika (2006) can be used to explore Baudry’s idea of whether or not a spectator blindly accepts the subliminal ideologies of a film through the way three of its characters experience motion.

The prisoners sit shackled, unable to escape or even turn away from the moving shadows on the wall in the allegory of Plato’s Cave. Jean-Louis Baudry, whose approach to film theory focused on psychoanalytics, took particular interest in the prisoners’ lack of movement. He asks, “Does [Plato] mean that immobility constitutes one of the causes of the state of confusion into which they have been thrown and which makes them take images and shadows for real?” (Braudy and Cohen 152). The possibility directly informs his apparatus theory, which asserts that because the average movie spectator is physically still, he or she is incapable of differentiating his or her own thoughts from the ideologies shown on-screen. This theory became widely influential, but it also drew criticism from theorists like Noël Carroll, whose film theory emphasizes cognitivism over psychoanalysis. Like Carroll, director Satoshi Kon’s film Paprika (2006) illustrates and challenges Baudry’s apparatus theory, both supporting many of its claims as well as revealing some of its significant exceptions.

Baudry claims that the filmmaker has power over the camera, just as the painter’s hand directly influences the paintbrush. In other words, it is impossible for the camera to be objective. The filmmaker inevitably spills subtle ideologies into the images projected on-screen. Furthermore, Baudry suggests that the average movie viewer is not aware of these ideologies and simply absorbs them at face value. A lack of movement is key to this subconscious exchange. To illustrate, he compares watching a movie to dreaming. In both situations, movement of the physical body is inhibited in darkness while the mind absorbs projected images. The immobilized viewer cannot test the reality of those images, which limits ideological autonomy (Braudy and Cohen 170). This spectator cannot control the events happening on-screen any more than he or she can control the events happening within his or her dreams. Specifically, the audience member is unable to distinguish between self and other. Baudry specifies that this undesirable condition gives the images and ideologies on the screen tremendous and harmful power over the movie viewer. Furthermore, it is primarily because the watcher’s movement is inhibited that he or she is unable to differentiate his or her own thoughts from the undercurrent ideologies being preached in the film. For Baudry, the solution to maintaining ideological autonomy is to acknowledge the apparatus. This could be as simple as turning around to look at the projector. In other words, recognize that the camera is not free from ideological influence. He says it is only once the viewer recognizes the messages within the film as outside of his or her own thoughts that he or she can reclaim the ability to either accept or reject them.

The film Paprika (2006) illustrates the legitimacies and faults of this theory in the way three of its key characters move. They each interact with a device called the DC Mini that allows psychiatric therapists to infiltrate a patient’s mind and project their dreams in an effort to identify the roots of anxiety or depression symptoms. The DC Mini is a parallel to Baudry’s non-objective camera, and the way these characters interact with the device reflects the theoretical role of filmmaker, film, and audience member. The film’s antagonist, the Chairman, an invalid confined to a wheelchair, gains control of the apparatus and exploits it to spread his own ideology. The titular Paprika embodies the apparatus, and consequently embodies dreams and films. And, the side character Detective Kogawa Toshimi achieves his own movement without the apparatus, aligning with those who doubt Baudry’s theory, specifically Noël Carroll.

In the beginning of the film, the physically disabled Chairman of Psychiatry uses an able-bodied avatar to steal a DC Mini and create a collective dream from their pooled subconscious. He does so as an act of rebellion anchored in his conviction that dreams are a sacred place, the last abode of privacy among humankind, which scientists and psychiatrists should not tamper with. His passionate hatred towards the DC Mini and the psychiatrists’ work is expressed in his statement, “This breath seethes in the joy of life. I will not allow arrogant scientific technology to intrude in this holy ground.” Hypocritically, he believes that granting himself complete power over all dreams will protect them from harmful outside control and the DC Mini gives him that power. While the exact means are vague, by inhabiting a body capable of movement, the Chairman is able to use the DC Mini to control the dream he shares with his avatar as well as access anyone else’s subconscious and easily pull them into his personal dreamscape against their will. Ergo, the Chairman effectively becomes Baudry’s filmmaker whose personal bias unavoidably influences his victims, the innocent audience, and without consent takes their intellectual autonomy captive to his.

The Chairman’s dream drives this home as it depicts a garish, ever-growing parade filled with cultural icons, appliances, and toys—all boisterously chanting nonsense. The parade multiplies as he forcibly enters the subconscious of more and more people, drawing them in. Once inside his dream, these victims lose their self-control, exhibiting the loss of autonomy Baudry fears. Within the dreamscape, victims transform into the objects from the parade: electric guitars, cell phones, golden statues, and more. No longer able to distinguish themselves from the procession, they fall victim to the ideologies of the Chairman, losing autonomy over both their thoughts and their movements. The effect spills into reality where they begin to gleefully spout nonsense, unknowingly harm others, and jump off of buildings without hesitation. They lose touch with their actual surroundings as they are engulfed in the projected images of the dream. The Chairman’s power grows with each individual absorbed into his inane carnival, which is shown in his increased subconscious ability to move for himself.

Inside the dreamscape, he is not only freed from his wheelchair, but he also gains the ability to change his form and size, move inhumanly fast, and eventually wield the power to destroy an entire city at a sweep of his arm. The Chairman’s free range of motion, dependent on the increasing number of his victims, is reflective of the ideological control the filmmaker has over the audience. He or she maintains subliminal autonomy over spectators by taking control of the apparatus, precisely as Baudry theorized. The Chairman is not the only character to support Baudry’s theory, Paprika does as well.

Paprika, a key player in the projected dreams, is a remarkably unusual character. She is the redheaded, subconscious identity of psychiatrist, Atsuko Chiba. Paprika’s introduction sequence reveals her stunning array of movement not only in comparison to the other characters in the film, but to anyone with a mortal body. She can move through images, as seen in the opening credits as she jumps through a computer screen, billboard, and graphic T-shirt. She can also manipulate motion outside of herself, causing traffic to freeze at the snap of her fingers. She has the same control over her body and the bodies of others that the Chairman gains through the DC Mini, suggesting that her liberation of motion similarly positions her as the ideological filmmaker. However, unlike the Chairman, she does not actively create dreams. She admits that in the realm of reality, as Doctor Chiba, she has stopped having her own dreams.

An additional important difference between the Chairman and Paprika is that Paprika maintains her power of motion as she effortlessly travels between dreams, the internet, and reality whereas the Chairman’s power is initially limited to the dreamscape. Most significantly of all, Paprika does not need the DC Mini to maneuver between these realms of reality and illusion. While the explanation of her existence is as vague as the connection between the Chairman and his avatar, her unique abilities are stated to be a natural side effect of Doctor Chiba’s prolonged exposure to the DC Mini. In a startling moment during the opening credits, Paprika turns to the camera and poses for the audience, revealing her awareness of her true identity. She is film itself, and all of the possible ideologies within that realm. By acknowledging her part in Baudry’s apparatus, she is able to celebrate her conscious and have complete intellective influence over others.

Yet, even Paprika experiences certain physical limitations when she willingly chooses to plunge into the Chairman’s dream to stop him. The Chairman sees Paprika’s autonomy as a threat, and once he discovers she has entered his dream, he puts all of his focus towards killing her. Eventually, he successfully captures and immobilizes Paprika, putting her in a confinement she did not anticipate. From this, she entirely loses her ideological influence over others.

The Chairman’s fear of Paprika and his obsessive need to contain and eliminate her reflects a possible loophole in Baudry’s apparatus theory. As film, Paprika represents the potential ideologies the filmmaker cannot control. If audiences are able to break out of the spell and reclaim their sense of self, they can interpret a film in whatever way pleases them, even if it directly contradicts the intention of the filmmaker. While this initially reflects Baudry’s answer to reclaiming ideological autonomy, Detective Kogawa, the third character, contradicts the theory by using a means to achieve freedom of interpretation different than acknowledging the apparatus.

Criminal Detective Kogawa represents an average film viewer through and through. He is Doctor Chiba’s patient because he struggles with anxiety from a recurring nightmare in which the unknown perpetrator of an unsolved crime barely eludes him in a chase down a long hallway. In this dreamscape, Kogawa feels the hallway warp in the middle of his desperate pursuit, buckling his knees and causing him to feel as if he is running through water. Every time he experiences this nightmare, his motion is limited and he fails to catch the perpetrator, or even glimpse his face. As a patient, Kogawa has no experience operating the DC Mini and, unlike the Chairman and Paprika, no ability to manipulate his dream. In fact, he relies entirely on Doctor Chiba (who appears to him as Paprika) to interpret his dream in their psychoanalytical sessions together. He seems to be Baudry’s theoretically perfect, ideologically dependent, incapacitated movie viewer.

However, in a pivotal scene, Kogawa begins to analyze his own nightmare while waiting for a therapy session with Paprika, who will not show because she has been captured by the Chairman. While reminiscing on the disturbing dream sequence, he discovers the root of his anxiety stems not from the unresolved case but from subconscious guilt about a past indiscretion. In his youth, Kogawa aspired to be a filmmaker with his friend but chose another path, leaving his friend alone and their passion project unfinished. His friend died shortly after this, before completing the film, and Kogawa subconsciously continued to carry immense guilt over it. On realizing this, Kogawa takes control of both himself and his thoughts and gains the ability to move between projected dreams. For example, after learning that Paprika is in trouble, he willfully and dramatically enters the collective nightmare and wrests Paprika from the Chairman’s grasp. He takes control of his autonomy and is able to differentiate his reality from the Chairman’s dream, unlike those lost in the parade. He even calls the self-righteous Chairman “disgusting” because he can see him through his own lens, immune from the influence of the filmmaker’s. After successfully rescuing Paprika, he returns to the final replay of his own nightmare where he victoriously shoots the perpetrator in the back, metaphorically finishing his long-abandoned film project. Kogawa develops the ability to move through dreams and manipulate his own dreamscape, frees Paprika, and conquers his own anxieties—all without both using and even understanding the DC Mini. To attain ideological autonomy and movement, he does not have to acknowledge the projector, as Baudry theorized.; he needs only to recognize and acknowledge the implicit meaning in his own dream. The movement which liberates him begins in his mind. As an audience member, he successfully conquers the filmmaker’s influence by reclaiming his own thought process, his own film, and the ability to interpret them for himself.

Kogawa’s experience as a viewer, perfectly illustrates Noël Carroll’s doubts about Baudry’s apparatus theory. Carroll is particularly skeptical of Baudry’s claim that film audiences cannot physically move. Carroll states: “Unlike Plato’s prisoners, the film viewer can move her head voluntarily, attending to this part of the screen and then the next. What she sees comes under her control, unlike the dreamer or the prisoner, in large measure because of her capacity to move her head and her eyes. And, the film viewer, as Baudry admits, can leave the theater, change her seat, or go into the lobby for a smoke (Braudy and Cohen 174).” By arguing that the spectator always maintains at least a degree of physical movement while watching a film, Carroll suggests that he or she retains some ability to decipher between the filmmaker’s projected ideologies and his or her own thoughts. He contends that viewers are inherently aware of the projector. Kogawa represents this natural movement and awareness. Kogawa’s story arc, like Carroll’s argument, directly challenges Baudry’s apparatus theory.

Baudry does not allow that some might be more easily swayed. He asserts that all are negatively influenced—like those misled into the Chairman’s gaudy parade. The film, Paprika (2006), supports this theory while, at the same time, demonstrating the exception. The way it finally resolves itself—through character motion—leads to the conclusion that, as Carroll argues, moviegoers do maintain a degree of ideological autonomy while watching films even if in a limited form. Awareness of implicit ideologies varies among viewers; however, everyone is capable of retaining some independent thought and sense of self while watching films—regardless of whether or not they physically turn around to acknowledge the projector. Autonomy, as Baudry suggests, is retained as it is actively chosen to be.

The dazed feeling a spectator experiences when walking out of a movie theater, or the slack-jawed faces of children watching Saturday morning cartoons, might make Baudry’s apparatus theory seem dominantly valid. Paprika (2006) seems to support his theory as well—but not entirely. The central question remains: in the subconscious exchange between filmmaker and spectator, whose ideology is in control? This quandary is as old as Plato whose escaped prisoner cannot make sense of his own reality except through the firelight of those who created the shadows he can no longer see.

Works Cited

Baudry, Jean-Louis. “The Apparatus: Metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in Cinema.” Film Theory and Criticism, edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen, 8th ed., Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 148-165.

Baudry, Jean-Louis. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Approach”. Film Theory and Criticism, edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohn, 8th ed., Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 217-227.

Carroll, Noel. “Jean-Louis Baudry and ‘The Apparatus.’” Film Theory and Criticism, edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen, 8th ed., Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 166-182.

Kon, Satoshi, director. Paprika. Sony Pictures Classics, 2006.

Plato. “The Allegory of the Cave”. The Republic, translated by Thomas Sheehan. Stanford University, 2007, pp. 514-517.

West, Palgrave, 2007, pp. 1-20.