by Brendan Lund

Thanks to the dream scene which occupies most of the running time of the film, Mulholland Drive, directed by David Lynch, can be read as representing the internal conscious and unconscious states of its protagonist. In this paper, I will argue that Mulholland Drive characterizes its protagonist using two mirrors of identity, the Jungian way in which she perceives herself in the dream (as opposed to how she really is) and the projection of Rita (an amnesiac stranger in need) that she subconsciously invents in order to try to fill her empty identity with the love of another.

Mulholland Drive, directed by David Lynch, is a film about obsessions and identity, and especially how one woman’s obsession becomes her only identity. In the film, the protagonist, Diane Selwyn, fantasizes about a return to innocence after failed romances and an unfulfilling acting career, as revealed by the dream sequence which occupies the majority of the film’s runtime. In Diane’s dream, we can see many of her character traits symbolized or projected by the characters which populate it. But in projecting herself onto others in the dream, it becomes apparent how empty her own personal identity is; the reflections there are merely hollow images. In this paper, I will argue that Mulholland Drive characterizes its protagonist using two mirrors of identity, the Jungian way in which she perceives herself in the dream (as opposed to how she really is) and the projection of Rita (an amnesiac stranger in need) that she subconsciously invents in order to try to fill her empty identity with the love of another. However, the film shows that in both cases the search for identity proves self-defeating, as it is an empty category, and such a search leads to thanatos, the death drive. Every step that Diane Selwyn takes to try to understand herself instead reveals more steps, stretching into an infinite regress. In her determination to fulfill the desire, no matter the costs, obsession turns into thanatos, leaving her between two deaths. As the majority of the film takes place within a dream, we will take into special consideration the work of philosophers and psychoanalysts (from Nietzsche to Lacan and Jung) who delve into the possible causes and meanings behind the content of our dreams. Combining this with noir theories of identity, this paper sets out to analyze the ways in which Diane Selwyn characterizes herself in her dream in order to reveal deeper subconscious truths about her character. In analyzing the tragic nature of Diane’s character, it becomes possible to comment on the problematic nature of the category of identity in general.

Who is Diane Selwyn?

Mulholland Drive is widely considered to be notoriously difficult to interpret, largely due to the fact that all but the last twenty minutes or so (of a two hour and twenty-minute film) occur in Diane Selwyn’s dream. The cues for this are extremely subtle: one of the first shots of the film is of the camera sinking into a pillow, representing falling asleep, and finally, near the end of the film a sinister character wakes her up.

These cues allow us to bookend the dream scene and separate it from the characterization of the real Diane Selwyn that we get afterwards. In order to consider who Diane is and how she sees herself, we will have to look at who she is during her brief portrayal in her waking life compared to the two versions of herself that she imagines in her dream, Betty (played by Naomi Watts), and Rita (played by Laura Harring). According to Carl Jung, dreams often serve to try to correct some deficiency of consciousness of which the subject is unaware (62). If we generally follow his theory for interpreting dreams, it allows us to read a certain teleology into the events of the film: since everything which occurs in the dream is a product of Diane’s imagination (and should thus be subject to her unconscious mental states), we can deduce from details in the dream certain important, and perhaps repressed, aspects of her character.

The real Diane Selwyn (again played by Naomi Watts), the Diane of waking life, is only presented to the viewer near the two-hour mark of the film and few details about her are given directly. The result for the viewer of such a revelation is deeply unsettling; we go from the most idealized version of Diane that she can conceive of herself, taking that to be the reality of the film only to discover that the real Diane is a bitter and hollow version of that ideal. We discover that Diane is a minor actress and ex-lover of a major movie star, Camilla Rhodes (again, played by Laura Harring), to whom she owes the little success she has had in Hollywood since Camilla used her influence to help her get parts in films. It is also apparent that Diane never recovered from her separation from Camilla and the hole it left in her sense of self-worth. Soon after Diane wakes up from the dream, a woman knocks on her door asking to pick up her things which she had left in Diane’s apartment. Coincidentally, the woman happens to look like a knock-off version of Camilla, a simulacrum of sorts. And it is apparent from the way the two women talk to each other, as well as the quantity of strangely mundane objects that the fake-Camilla has come to collect, that the two of them were likely in a romantic relationship which did not end well.

It stands to reason that perhaps Diane began seeing this woman in an ill-fated attempt to make Camilla jealous, as one of her major frustrations as a character is the fact that Camilla held all the cards in their relationship. Whereas Diane depended on Camilla for almost everything, her career, her sense of self-worth, her purpose in life, Camilla has all those things independent of Diane. Camilla is a successful actress in a fulfilling relationship with the director of the film she in which she stars; she moves on from Diane with little to no consequence. Diane’s relationship with Camilla is characterized by strong negative desires—i.e. she desires that Camilla desire her—but the trauma of their separation and horror of reality constantly frustrate those desires, which are then manifest symbolically in her dream. Her obsession with Camilla becomes her only identity, but in pursuing that obsession, Diane is constantly confronted with the reality that she has built her life on a lie and that no amount of love from Camilla could fill the void which is her self. This subconscious obsession eventually turns on itself and forms the content of the dream in a search for Diane’s true identity, if there is such a thing, manifesting itself symptomatically as the two images she forms of herself in the dream, Betty and Rita.

Diane Selwyn: Betty

Betty represents the idealized version of how Diane sees herself, but in many ways is everything Diane is not. The first time we see Betty, she is smiling and looking around excitedly, in awe of the world around her and its infinite potential. She is a naive aspiring actress arriving in L.A. for the first time with her whole life ahead of her. Contrast this to the first time we see waking life Diane Selwyn: she is bitter, angry, and self-destructive. In a Freudian psychoanalytic sense, Diane is regressing in this dream, returning to the time when she was happier and more innocent (Freud 295). More than anything, it shows us that Diane wants to forget; she would rather live a happy fiction than confront the horrors of her reality. In this way, Betty’s character mirrors Friedrich Nietzsche’s analysis in The Birth of Tragedy between the Apollonian and Dionysian world views. According to Nietzsche’s interpretation, ancient Greek tragedy came about as a synthesis of the ideals represented by these two gods: Apollo represents order and reason but also useful fictions we tell ourselves, whereas Dionysus represents the madness and chaos that ensue when we confront the horrors of reality (7). Under this reading, Betty’s experience in the dream starts out very Apollonian but ends up quite Dionysian. The dream begins with many useful fictions that Diane has made herself believe to try to rationalize and explain her waking life situation. In the dream she comes to LA to live with her aunt who is apparently well connected in Hollywood and will be able to help her get auditions for big roles. Much later in the film, however, after Diane wakes up she reveals that her aunt is actually dead and so no such connection ever existed. This imagined supportive relationship with the aunt serves as a projection of her subconscious mind in order to try to explain the disparity between the way she sees herself and the way the world sees her.

Diane never made it on her own as an actress, and so she creates this fantasy world in which her aunt is still alive and supportive as a way of excusing herself from her perceived failures (meaning that if her aunt were still alive, she believes, things could have been different). To quote another passage of Nietzsche from his book The Gay Science, “Everything that is of my kind, in nature and in history speaks to me…everything else I don’t hear or forget right away. We are always only in our own company” (135). Diane refuses to cope with the disparity she sees between her ideal self and her experienced reality, and so the greatest fiction she invents in the dream is the character of Betty, a happy and innocent version of herself with the potential to do anything. Her waking life experiences do not correspond with that vision so she discounts any new information which disagrees with her ideal view of herself, creating a sort of self-referential echo chamber.

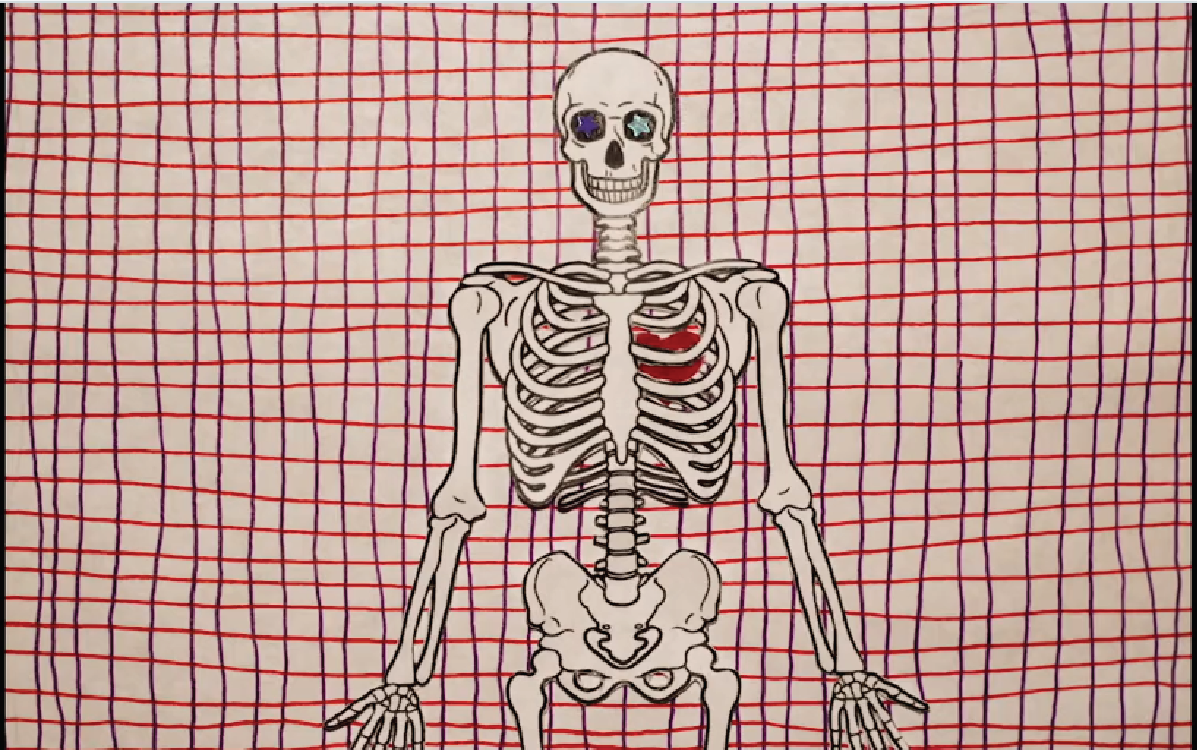

This counterfeit sense of identity is built on her desire to be loved by others (e.g. desired by directors as an actor, desired by Rita romantically, etc.) which leads her to form a weak sense of self, dependent on the fickle approbation of those around her. But the horrific and maddening truth that she seeks to escape is that she not desired, or at least not by Camilla anymore. These truths inevitably begin to creep in in a very Dionysian way as Betty follows the threads of those negative desires until the climactic moment in which she sees her own hollow and dessicated corpse. The hollow and empty nature of the corpse mirrors Diane’s internal state and foreshadows her ultimate demise: as long as Betty lives, Diane Selwyn is dead and since Diane is unwilling to give up the fantasy that she has built her identity on, the corpse in the bed is literally her own.

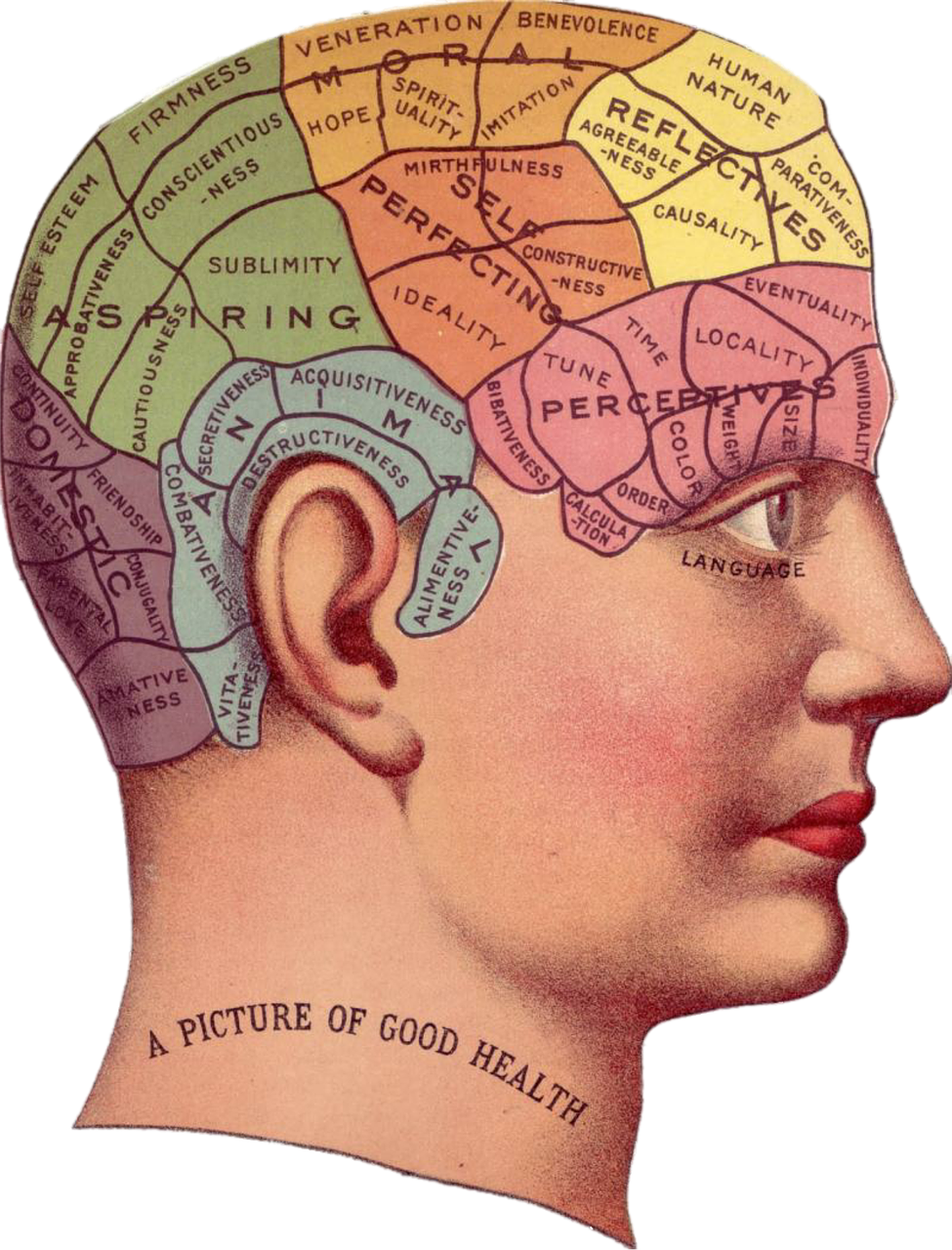

We can also see projections of Diane’s subconscious in the way Betty interacts with the other fictional characters of the dream. Since Betty is everything Diane is not, and since Diane is a mediocre actor, it stands to reason that Betty would be a great one. In this way, Betty comes to represent Diane’s idea of how acting should be and consequently reveals Diane’s own poor understanding of what it takes to succeed in that industry. This is exemplified by the over exaggerated facial expressions which Betty uses to communicate with everyone, especially during the scene in which she practices her lines with Rita. In this scene, Betty is dynamic, moving around the room and shouting her lines while Rita is reading the lines from a script in a painful monotone. This scene serves to invert the reality in which Camilla is by far the better actor compared to Diane and is a projection of her own insecurities concerning her abilities, closely mirroring the Jungian conception of the Shadow Self. According to Jung, the Shadow Self is the subconscious component of our identity that is normally characterized by traits which in fact belong to us but which we fail to identify in ourselves (62). Jung claimed that when the Shadow Self is repressed, it leads to projecting its negative qualities onto others, but conversely, when it is understood and accepted, it can be a great source of creativity (ibid). Betty’s overacting thus demonstrates a strongly repressed component of Diane’s Shadow Self which simultaneously causes her to project her insecurities and precludes her from being able to reconcile them through a genuine acting performance.

Take for example the scene of Betty’s audition. During the audition, Betty throws herself at a much older man in an almost insane way, almost pornographically. She over exaggerates every movement and even the dynamics of her voice, moving from a frustrated and assertive yell to a disturbingly seductive whisper. The scene is made extremely uncanny by the fact that so many people (men and women) watch it as if it were totally commonplace and there is definitely a powerful feeling of empathetic vulnerability for Betty on the part of the viewer. However, as this is Diane’s fantasy, of course everyone loves her acting, further demonstrating a disjoint between the dream and reality, a disjoint which the viewer now begins to sense because of the dehumanization of the audition. The only person who offers a meaningful critique of her performance is the director who calls it, “a little forced,” but he is characterized in the dream as being so obtuse as to be impossible to understand or take seriously. As this entire scene is the product of Diane’s imagination, it reflects the insecurities of her Shadow Self and her desire to be desired by others. But because Diane focusses so much on what others think about her, she has little value for herself and so inadvertently creates the insecurities she is trying to overcome by proving herself to be a great actress.

The real mystery of the film is unraveled through Betty’s process of inadvertently discovering the truths about her own identity, which ultimately leads to the dissolution of the dream. In many ways, Betty is like the detectives of the noir genre, but instead of trying to solve a crime, the only question she has to answer is, “Who am I?” In her book, Shades of Noir, Joan Copjec compares the classic, objective detective (like Sherlock Holmes) to that of the noir genre and states that, at least in the case of the classical detective, the investigation is ultimately about the establishing of identities (e.g. identifying the killer). Detective work then, “scrutinizes, it invades, but above all, it constitutes the very people into which it comes into contact. It ‘makes up people’” (171). What makes the noir genre unique is that the detective is often not an objective observer in this process of identifying but rather becomes swept up as a subject in the same investigation (184). In this regard, the mystery that Betty has to unravel is not a chain of clues leading up to a murder but rather the chain of signifiers which lead her to her own identity; the unknown suspect she pursues turns out to be herself. Betty, like the noir detective, is not an objective observer but rather an embodied participant within the events of the dream, and as such, is subject to causes and occurrences within it. This embodiment of the subject causes her to lose her radical freedom and demotes her from an objective subject to an object, just like all the other objects of the film, subject to fate.

Diane unconsciously feels that her life is governed by circumstances outside of her control and so she dreams up an elaborate, shadowy conspiracy to explain why she does not get the lead role and also to motivate her need to keep Rita to herself. In the dream, the director of the film she wants to be in is forced by sinister figures to cast a particular girl (not Betty) in the role without even auditioning her. The film portrays him as being reluctantly coerced by the same anonymous conspiracy into accepting the decision and so removes guilt from him for his decision as well by blaming it on coincidence. It is significant then that when Betty shows up to the sound stage to audition, she and the director make prolonged eye contact, implying that there could be something between the two of them if it were not for the conspiracy which constrains their actions. This is another example of how Diane Selwyn projects herself into the dream; she cannot come to terms with the fact that her fantasies of becoming a famous actor never came to fruition, and so she invents nameless antagonists who secretly close the way before her, and by excusing the director’s actions through the invention of the conspiracy, she simultaneously attempts to excuse herself from responsibility for her own role in the events that lead her to her current misery.

Diane Selwyn: Rita/Camilla Rhodes

The second mirror of identity that we see in Diane’s dream is her characterization of Rita (played by Laura Harring, the same actor who plays Camilla Rhodes in waking life), the amnesiac woman on the run with nobody to turn to. Because Rita is an amnesiac, she is a “subject qua void” (as Slavoj Zizek would say), a blank slate onto which Diane can project herself and an idealized version of what she is looking for in a relationship (220). It is interesting then that Diane conceives of this ideal relationship with a latent power structure which places her over Rita and makes Rita indebted to her. Rita does not know who she is but believes she may be in trouble with bad people, and so Betty, instead of taking her to the hospital or the police, decides to keep her for her own. This hierarchy of power between the two of them is an inversion of the one that Diane experiences with Camilla in real life and reflects Diane’s desire to feel needed.

Betty’s relationship with Rita is typified by what Alexandre Kojeve would call a negative desire, or a desire whose object is not the beloved (Rita herself) but rather desire itself (99). Betty’s defining desire is to have Rita love her, but she confuses the corporeal satisfaction of that desire with genuine love. As Kojeve points out, “Born of desire, action tends to satisfy it, and can do so only by the “negation,” the destruction, or at least the transformation of the desired object” (ibid). Betty’s desire to be loved by Rita leads her to act on it, consummating the desire with a lesbian relationship. But since Betty has failed to understand the true object of her desires (Rita’s love, not Rita herself, and more importantly, the hole in her self-worth that this love fills), this consummation is more of a consumption; it forces Rita out of existence by subsuming her into Betty. The result is a blurring of the distinguishing categories between the two of them (blonde/brunette) which renders them ultimately identical and satisfies the negative desire by destroying it. Because Betty is so focussed on her need to be loved, she can never see from the perspective of the other, and so sees Rita as a means of satisfying her desire, rather than a person with intrinsic value of her own.

The fact that Betty and Rita become identical towards the end of the film also becomes the means whereby the viewer comes to realize that the quest for Rita’s identity is really the quest to find out who Diane Selwyn is. In this case, Diane’s obsession for Camilla Rhodes is transposed into the dream as Betty’s desire to help Rita discover her identity and she follows the trail of clues with the same single-mindedness that Diane focusses on her obsession. However, with each step they take to try to uncover Rita’s identity, it seems to withdraw one step further away from them, culminating in the corpse scene mentioned earlier. The problem here, as Jacques Lacan pointed out, is that people base their identities on symbolic fictions taught to them through the use of language. As a person tries to pin down the meaning of those symbols, they are forced to appeal to the use of other symbols, thus creating an infinite regress of chains of signifiers. Lacan argued that the content of that symbol, “I,” is ultimately empty, due to its nature as a signifier, or “a sign which refers to another sign,” but never to an object (Seminar III 167). Instead, he explains identity formation with his theory of the mirror stage in which we come to form our concept of identity when we begin to recognize our image in the mirror with the help of our parents and language (Seminar 8, 353).

The film reflects this idea in the fascinating way in which Rita comes to form her own identity after losing her memory. In the first few moments after the accident, she staggers around aimlessly without speaking to anyone and has no concept of self; then when she is confronted with Betty, she is able to participate in the conversation with the pronouns, I and you (both signifiers). It is this conversation which clues her into her need to identify herself to Betty, to come up with some reasonable story as to who she is and how she got there. As she looks for inspiration, she recognizes her semblance in the image of the woman on a box of hair dye (like recognizing herself in a mirror), and picks the name Rita, after the name on the box. So from the beginning, the question of Rita’s identity becomes hard to answer in that she is caught up in a chain of signifiers. In answer to the question, “Who am I?”, we are given the answer Rita, but this fails to satisfy as the signifier “Rita” merely replaces the signifier “I” in the question with neither of them pointing to a concrete object. In fact, the chain of signifiers becomes even more tangled up as later in the film, Rita remembers the name Diane Selwyn and assumes it must be her own. They set out to look for Diane Selwyn which is ultimately where they find the corpse, and from there on, Rita wears a blonde wig, highlighting her transformation into Betty. The real Diane Selwyn’s narcissistic obsession begins to intrude on the fantasy of the dream once their two identities become indistinguishable. In searching for Rita’s identity, the chains of signifiers derail Betty into searching for her own and reveal the fragile mental state of Diane, the author of the dream. And yet this revelation is still unsatisfying as even the name “Diane Selwyn” is yet another signifier without object and so we are left with ouroboros, the self consuming snake. Betty is Camilla Rhodes, Camilla Rhodes is Rita, Rita is Diane Selwyn, and as the film reveals at the end, Diane Selwyn is Betty. Diane’s sense of identity is so problematic because, in her mind, the ideal version of herself is not herself, but rather Camilla Rhodes, and so in her very effort to establish Camilla’s life as her own identity, she destroys herself.

Results of the Obsession and a Possible Cure

The way that this film addresses the problem of chains of signifiers in identity is so illustrative that it even made it difficult to write this paper, since it is very difficult to refer to any one of the characters and have the reader understand to which one I am referring. What if I use the actors’ names, Naomi Watts and Laura Harring? These two become signifiers to add to the circular chain as each actress plays multiple parts in the film, representing in turn both Camilla Rhodes and Diane Selwyn. On top of this, David Lynch adds his signature doppelgangers to the mix (it is interesting to note that this film was originally written as the pilot to a spinoff series of Twin Peaks, where doppelgangers feature heavily) so that not only does each actor play multiple parts, but many of the parts are played by multiple actors. This brilliant confusion of signifiers only serves to make the chain more elaborate and obscure; we as audience members experience the same kind of confusing chain chain of signifiers in watching and interpreting the film as the characters experience in their circular impulse towards self-awareness.

The circular chain of signifiers elaborated above serves to demonstrate the self-consuming nature of Diane’s obsessive negative desires. In seeking the affection of others, Diane is really trying to justify her own existence to herself, but the sad truth is that her desires will constantly be frustrated. Copjec claims that what noir denies, “is the possibility of deducing the criminal from the trace,” and necessarily treats consciousness the same way (178). We often seek to establish our sense of identity based on the “traces” which others leave us, such as their affection and approval. This serves as evidence to us that our own lives are valuable, but noir reveals that the logical connection between those evidences and what we claim they entail (a meaningful sense of “self”) is untenable. Diane’s ill founded obsession with Camilla leads her to a death drive because it reveals to her that as long as she bases her identity on others, it will remain an empty category, and yet she refuses to accept that fact. Instead she chooses to live as a walking corpse between two deaths, visibly dead on the inside but continuing to live in a vain attempt to satisfy the hollowed out remains of her consummated negative desire (Žižek 21). This theme is also reflected in the paradoxical chronology of sequences of dreaming and wakefulness in the film. The movie starts with descent into the pillow, the start of the dream. From there, Diane is woken up in her bed in the same room and position in which Betty and Rita had seen the corpse. Then at the end of the film, Diane, unable to cope with the meaningless of her life, kills herself and it becomes apparent that hers was the corpse she had seen in the dream.

Thus Diane is doomed to endlessly follow the faulty reasoning of the chains of signifiers with which she identifies herself, forever striving to capture the object to which none of them refer: her self-worth. Each night she sleeps the sleep of death, perchance to dream of a different world in which roles may have been reversed and in which she might have been fulfilled. However, the dream cannot sustain itself by striving to be someone else; Diane can never be herself, precluding that fulfillment from ever arriving. She awakes in the cold harsh light of reality as empty as the day before since the meaning she seeks in life is constantly deferred, and so when she cannot stand it any longer, she escapes once more into death only to start the process all over again.

Diane exists as a closed loop with regard to herself because her narcissism has left her with no choice but to make herself judge, jury, and executioner to her own sentencing. The fact that she kills herself at the end, turning herself into the corpse which she saw earlier, shows that she is the cause of her own demise. If however, she were able to break any step in the chain of signifiers, she would in turn break the entire mechanism which keeps her wheel of self-destruction spinning. Slavoj Žižek advocates an open awareness of the problematic nature of the category of identity. According to the Slovenian philosopher, realizing that our identity is based on these negative desires for the approval of others and that these are necessarily empty due to the access problem of consciousness, allows one to break the chain and live a more genuine life (Looking Awry, 35). However, once our dependence on symbolic fictions to form identity has been broken, it is not clear what kind of life will remain, or how we would derive meaning from it. What if, for example, Diane Selwyn had been able to come to realize the emptiness of her obsession and break the cycle of thanatos in which she finds herself? What would she use to give her life meaning then? In this case, the only option that remains is to live your life in the moment, as a series of becomings rather than beings. Perhaps Diane would have come to love the small roles that she was able to be involved in, or perhaps she would have formed new and healthier relationships in her process of healing after Camilla. In this regard, Mulholland Drive beautifully represents the paradoxical and counter-intuitive nature of identity. In her obsession to justify her own existence, Diane inadvertently rendered it an empty category but had she simply lived her life with the perspective that existence itself, and the experience it provides, has an inherent value, then she would have never had to stop to ask where that value comes from in the first place.

Works Cited

Copjec, Joan. “The Phenomenal Nonphenomenal: Private Space in Film Noir.” Shades of Noir: a Reader, edited by Joan Copjec, Verso, 2006.

Copjec, Joan, and Slavoj Zizek. “’The Thing That Thinks’: The Kantian Background of the Noir Subject.” Shades of Noir: a Reader, edited by Joan Copjec, Verso, 1993, pp. 199–223.

Freud, Sigmund. A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis Translation with a Preface by G. Stanley Hall. Boni & Liveright, 1920.

Jung, Carl G., and Marie-Luise von Franz. Man and His Symbols. Doubleday, 1964.

Kojeve, Alexandre. “Introduction to the Reading of Hegel.” Deconstruction in Context: Literature and Philosophy, edited by Mark C. Taylor, University of Chicago Press, 1998, pp. 98–120.

Lacan, Jacques. “Seminar 3.” The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, translated by Cormac Gallagher, S.n., 2002, pp. 29–43.

Lacan, Jacques. Transference: The Seminar of Jaques Lacan. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. Translated by Bruce Fink, 1st ed., Polity, 2015.

Lynch, David. Mulholland Drive. 2001

Nietzsche, Friedrich. “The Birth of Tragedy.” The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings, edited by Raymond Geuss and Ronald Speirs, Cambridge University Press, 1999, pp. 1–116.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science. Edited by Bernard Williams. Translated by Josefine Nauckhoff, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Zizek, Slavoj. Looking Awry: an Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture. The MIT Press, 2000.